Michelle is a child in the clutches of a heroin addict and sometime tyrant who also happens to be her mother. The drug scene is a living hell it’s almost impossible to imagine existing in Switzerland. Her mum threatens to kill herself every time Michelle mentions leaving. The young girl shoplifts and picks up heroin for her mum. She is verbally, mentally and physically abused. Her mum goes into prostitution. The nightmare seems never-ending.

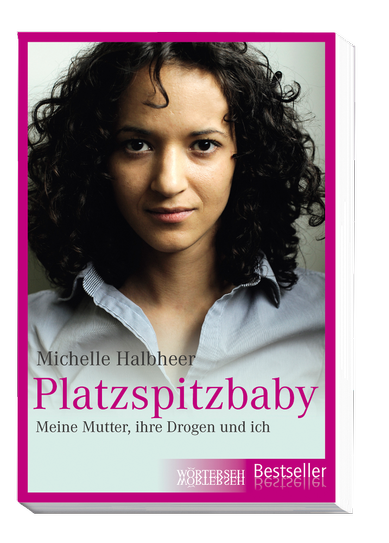

With help from her father’s family, her own bravery, and plenty of miraculous luck she escapes with her health intact. And in her late twenties she writes a book about it, which translates as Needle Park Baby: My Mother, Her Drugs and I.

So much for my jolly Christmas reading.

Left, the memoir; right, Michelle Halbheer at publicity for the movie with the actresses who play versions of her (Luna Mwezi) and her mother (Sarah Spale). Photo from Radio Top.

The memoir is flooded with details of the domestic life of a heroin addict with severe mental health issues, and the horrors of a childhood under her thumb. We get vivid depictions of the drug scene in and around Zurich in the 1990s (especially at Platzspitz, aka “Needle Park”, and a “drug house” in a town not far from where I live). The tone is sometimes melodramatic and moralizing but always rich with lurid detail and often moving. It’s the most harrowing sustained account of child abuse I’ve read.

I was ready to dislike the film version. I wanted a dark indie movie, but this was a big C-Films hit starring Sarah Spale of Wilder. The movie’s website offers tie-in teaching materials for younger teens. I figured everything would be sanitized, sentimental, written for idiots and poorly acted. I only watched it because it was successful, y’know, in the discourse.

Turns out I’m a stupid snob. In fact the film does a really good job of getting a coherent screenplay out of the litany of trauma documented in its source material. It refines things down to a short passage in the life of Mia and her mum in which a solid, satisfying arc can spin out while keeping up sharp, realistic dialogue and even some dark humour.

My viewing partner and I were both convinced; Spale is transformed from her Wilder days, and Luna Mwezi fantastic in the lead role. It’s a tense, exciting movie which builds a lot of sympathy for our heroine without dehumanizing her mum. You could argue it beats the book for taking a less moralizing approach. Add into that a really nice transposition of the locations and look of the Nineties heroin scene into filmworld, and a musical subplot that stays loosely true to life while tugging at the heartstrings just the right amount, and you have a winner.

All in all, I’d recommend the film without reservation. The Needle Park years aren’t accessible to new arrivals in Switzerland, but they ended only 25 years ago. Heroin was everywhere, its victims shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the world’s richest financiers. How mad is that?

For those who want to go deeper, seek out a copy of the book. It will tell you how race played a much greater role in the family’s trauma, how the Free Church screwed everything up repeatedly, and how in reality Michelle amazingly, marvellously, gets the hell out of hell.

Swissness Difficulty Level: Chasseral (easy).

Language: Swiss German.

Availability: PlaySuisse and most normal streaming services in CH; if anyone finds an English version accessible abroad, please contact me and I’ll link here.

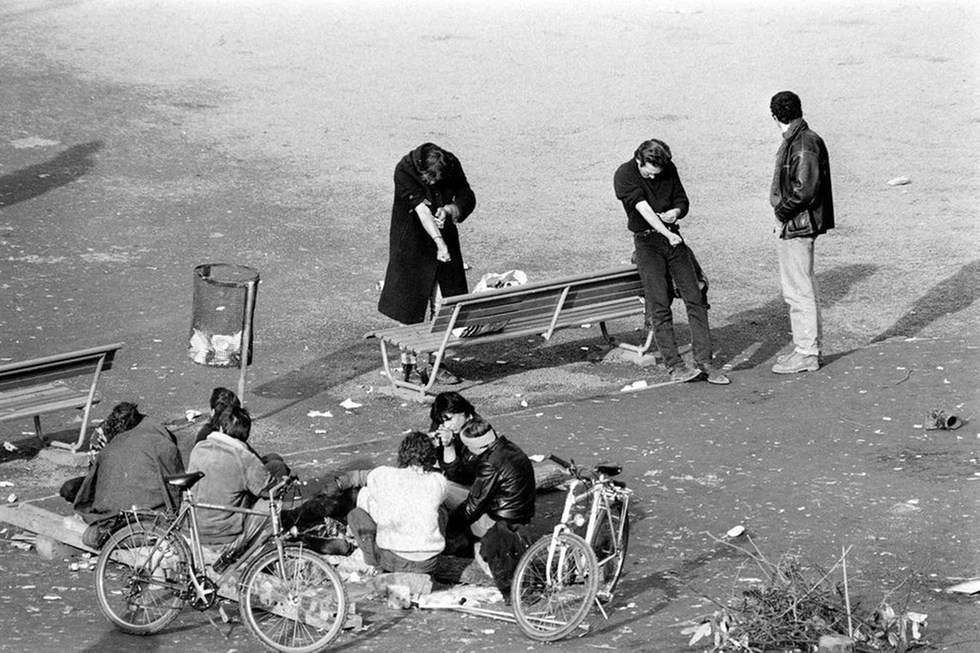

Swissness Lab Report: Heroin 1 – The Crash

Platzspitzbaby‘s grotesque opening scene sees Michelle wandering through the Bosch painting that was Platzspitzpark in the early Nineties. It’s directly next to the train station, behind the Swiss National Museum. Living near Zurich and working there as a young person, I’ve spent hours around these areas – reading quietly, in a trendy bar at Letten or even going for a swim. Before I researched the topic of heroin I never suspected the gravity of what was taking place there only thirty years ago.

This short explainer outlines the historical events which led up to Platzspitz. Much of this comes from descriptions by the doctor and activist André Seidenberg; more is to be found on the Platzspitzbaby website, and still more is around Youtube in the form of SRF documentaries. My main references are listed at the end as usual.

Prelude (1951-1967): Morphine and International Accords

1951 is the water mark for drug law. The Swiss Bundesrat implements the Betäubungsmittelgesetz (Narcotics Law) and bans the the medicinal use of cocaine and heroin. They do this because of international pressure resulting from anti-drug scourge policies, especially in the USA. In Zurich only a few doctors and medical staff keep using opiates in private, along with a few dozen so-called morphinists based around Niederdorf.

In 1961 Switzerland signs up to the UN’s International Convention on Narcotics Laws. The country’s adherence to the War on Drugs, and thus a repressive view of drug consumption, is in place.

Act One (1968-1979): Counterculture Sours

The student riots of 1968 hit much harder in France and Germany than they do in Switzerland, but a counterculture grows out of it. Switzerland is remains extremely conservative in many ways. Users of psychedelics and weed are harshly stigmatized; drug use is seen as tied up to the blossoming anti-authoritarian left-wing counterculture, a rather self-fulfilling prophecy as the police crack down.

The AJZ (Autonomous Youth Centre of Zurich) springs up, the result of a decade of pressure on the stiflingly old-fashioned, bourgeois city. It soon begins sheltering addicts of the new drug in town, heroin, who are regarded as vermin by the agents of those repressive drug attitudes that have been building up.

In 1972 comes the first recorded death from heroin.

By 1975, fifty-two have died of overdose. Drugs are slowly but surely no longer just a “youth problem”. By now, hepatitis has been discovered and associated with needle use. But something far worse is coming.

Act Two (1980-1986): Drug Policy Wars

Tschönkiraum [Junkie Room] is open when the whole AJZ is in use (restaurant etc.)

From now no more medical support

Tschönki meeting, Thursday 8pm in the Drug Room

Photo: Vogler, Gertrud: Zürich/Signatur: Sozarch_F_5107-Na-09-126-023 (from Sozialarchiv).

HIV hits hard in the early Eighties, not least in the AJZ “Fixerraum”, where needles are shared. The nature of the new virus means sex worker addicts unwittingly multiply the potential for infection amongst the heroin-using population.

From the police side, the War on Drugs is in full swing. Dealers and groups of users and addicts are pushed from one public area of the city to another by police. The rule of law is clear: punishment to drive out the scourge. But it isn’t working; and the accompanying social policy is terribly flawed.

In fact, the dominant paradigm from psychiatric authorities is abstinence. Cold turkey, goes the theory, is the only way for addicts to stop for good. We know now this is simply wrong. But the other paradigm, harm reduction, is very hard to get through. Voices against it are fuelled by ignorance and purity morality, hardened by decades of War on Drugs rhetoric from those earlier accords.

I shouldn’t be too harsh: I’m sure a lot of Swiss had plenty of fear and misconceptions about heroin. Many people did not grow up around users or addicts, or encountered only, as I did, as smelly, scary homeless people begging in town centres. And the dope-fiend tropes of the War on Drugs have always been easy to digest for nice middle-class rule-followers with a puritan streak, or at least those who aspire to that.

Things come to a head in 1985-86 in the so-called “Needle Exchange Wars” over whether medical personnel can distribute the needles which so clearly save people’s lives, and whether police can take away those clean needles. Eventually the harm reduction people get their way, a victory that opens the path to homeless shelters and other forms of easy-access medical care.

Harm prevention policy slows the waves of HIV and hepatitis. But alone it can’t stop the scene spiralling, since the war is still being waged by police. Addicts and dealers are still getting shepherded from place to place. (For people who know Zurich: typical hangouts were Central, Hirschenplatz, the Rondell at Bellevue and the “Riviera”, slang for the banks of the Limmat at Bellevue. I was interested to note all of these places were close to, or between, the train stations at Stadelhofen and HB.)

Finally, from 1986, the police decide to leave one small but important area of the city to the miscreants. They give up regular checks of the Platzspitzpark. The scene that settled there is to become the hell on earth of the opening scene of Platzspitzbaby.

Act Three (1986-1995): Needle Park and Bahnhof Letten, Hell on Earth

Here are some facts I’ve found out about the scene that sucks in Michelle Halbheer’s mum:

- At its peak, 3000 people travelled through Platzspitz per day…

- …200 of whom spent the night.

- The location is perfect for users, dealers and addicts. It is next to the central station, connecting it to both the whole canton and all of Switzerland via the famous Swiss train network – as well as key stations in local countries. Its various entrances mean it’s easy to visit anonymously for the briefest moment, and easy to flee from. Thousands of people are permanently passing through.

- The milieu attracts every conceivable level of society. Bankers used to go to Platzspitz in a suit, shoot up, then leave after half an hour to go back to work. One way to earn yourself a shot is to work as a guide between the men in suits who come to the entrance and the dealers in the depths of the park.

- Filterlifixer carve out another bizarre role in the drug market. They’re a certain kind of market stall salesperson, offering paraphenalia and water on makeshift stands or sequestered carts. They exploit the fact that heroin injectors put cigarette filters into the spoons to soak up any larger particles before drawing up the liquid in the syringe. Their “payment” for providing the paraphenalia is to collect those cigarette filters for the heroin residue they contain. 10-20 are needed for a shot. All the Filterlifixer are positive for HIV, hepatitis C or both.

- The toilet cabins in Platzspitz are converted into medical quarters, where two nurses and a doctor are employed between 7am and 11.30pm.

- Between November ’88 and Febrary ’92, 7 million syringe-and-needle sets and 2 million extra needles are handed out (one news report refers to around 10,000 clean needles given out every day).

- In the same time span, 6700 artificial respiration measures are carried out to save people from respiratory arrest which stems from heroin’s effect of slowing down breathing. At the peak, twenty to thirty resuscitations take place per day.

- In 1991 alone, a total of 21 people die in the park itself.

- The nights are dangerous for the medical staff. Drug gangs move in, notably (but not only) from Albania and Nigeria. By the end murder by stabbing is a very common occurrence.

- During this period, drug use is the number one cause of death of people in their thirties and forties.

In 1992 Platzspitz is “geräumt” (evacuated/cleaned out), but the social system and policy isn’t yet ready to absorb profoundly traumatized addicts, nor stop the flow of heroin. Everyone heads to the old train station Letten, where conditions are even more inhumane.

In Switzerland as a whole, the estimated number of people injecting heroin are:

1976: 4,000

1985: 10,000

1988: 20,000-30,000

Numbers plateau and finally begin reducing in the mid-nineties, when methadone substitution programmes are rolled out en masse.

Epilogue (1995-2000s): The Last Heroin Punks

The story goes that, following the final clear-out of Letten in 1995, the social and medical services were much more prepared, and their radically progressive drug policy changes genuinely worked. I’ll look at the successes in more detail in a later essay.

But there were still casualties. The following text appears in the movie:

One of the biggest public drug scenes in the world existed in the centre of Zurich for nearly ten years.

On 14th February 1995 the addicts were forced out and sent back to their home boroughs.

Half of those boroughs were completely overstretched.

Overstretched from the addicts…

…and from their children.

The real Michelle Halbheer was born a few months before me. As a child she caught the tail end of the crisis in the city; as a teen she suffered the consequences of slipping through the net when Bahnhof Letten was “cleaned out”.

The last hold-outs against the system congregated in “drug houses” in the country like the one depicted in the movie, ignored by the overworked and sometimes ideologically misguided local authorities. Michelle’s mother did receive medicinal methadone treatment, but she got it from a weird pastor in a Free Church which also helped her keep her child captive.

So is it the addict’s fault, or is the system? In her book, Michelle Halbheer does take aim at various aspects of the system, notably the church and various social services; but she underscores that does not let her mum off the hook, as an individual with agency in the world. The book, if not the film, can be read as vehement attack on a profoundly abusive human being.

But in spite of the many abuses, it’s not easy for me to judge addicts for still seeing the system as the enemy, after decades of being beaten, repressed and simply ignored, and running into the arms of church groups and addict pals who enable her but offer some kind of warmth in return.

The main moral take-home of my research, then, is that it’s easy to lose one’s sense of humanity of the individuals caught up this history of drugs, and a useful exercise in being a good human to inform oneselves of the wider context in which they move.

Watching a film like Platzspitzbaby is a good place to start.

References

Platzpitzbaby: Meine Mutter, ihre Drogen und ich, Michelle Halbheer (2013, German)

Platzspitzbaby video supplement materials from https://platzspitzbaby.ch

Articles in English by André Seidenberg at https://seidenberg.ch/english/:

The Bloody Eye of Needle Park Stag (reading sample)

“The Platzspitz Junkie Hell Still Haunts Me” (translation of article in Das Magazin)

Brutal video interview with two survivors of the Platzspitz scene (German): https://www.20min.ch/story/in-wunden-voller-maden-suchten-sie-nach-venen-319874023622

Decent brief history of heroin in Switzerland, especially in Zurich (German):

https://www.sozialarchiv.ch/2017/10/27/vor-25-jahren-die-schliessung-des-needle-park/

I’ll look this one up, sounds interesting! B.

LikeLike

Do it! And please let me know if you find an English language streaming version and I’ll put a link in the article. Ta

LikeLike