Snow-blighted Alps loom over grey tower blocks in the small town of Chur in Graubünden. It’s the 1980s: the world is changing, European metropolises are only a train journey away, and teenager Martin Felix finds small-town life ridiculous.

Martin is a super-smart kid with a gift for pithy critique of the banalities of backwater life. The Gymnasium is easy for him, so he spends his adolescence writing, making art, playing music, and experimenting with drugs.

Martin is an outsider. Maybe, as his mother will later hint, he has a fatal weakness for seeing himself as “special”, a desperation not to be “average”. But he’s not antisocial, or even a loner: he surrounds himself with other friends from outside the norm, whom he loves dearly.

With his friend Ivo, for example, he smuggles two kilos of hash from Amsterdam on the train into Switzerland, and deals it in the local park. At their high school graduation party, Martin and Ivo take LSD for the first time. Soon after, they smoke heroin.

Before they go to Uni, Martin travels with Ivo and a pal on a road trip in France. Suddenly Martin whips out a needle. He reveals he injects heroin now, since it’s cheaper.

Zaunkönig documents Martin’s life as it descends into multiple addictions, eventually leading to his death in 2005.

Plenty of this addiction tale turns on interviews with Martin’s friends and his parents. Attention is also given to the bleak Alpine landscape; I was reminded that the translation of Graubünden is “Grey Leagues”. It’s a sad tableau of a life revolving around around the shady corners of a Stadtpark, so typical of Swiss outsiders during, and in the aftermath of, the Platzspitz years.

What elevates Zaunkönig is that its writer and director is none other than Martin’s hash-smuggling companion Ivo – Ivo Zen, who we’ve seen on this blog already (Suot tschêl blau, 2020). Zen has large amounts of filmroll of Martin, who starred in a graduate film he made, and uses it smartly to bring the portrait alive. The grainy footage emphasizes the historicity of the story, and slips into ambience when the text should comes to the forefront.

As for the text – Zen was granted full access to Martin’s diaries, which are fascinating. The film shines brightest when it focuses on these school notebooks, both their contents and their materiality. In parts Martin compulsively writes over his own words; he obsessively colours in the squares of the maths book to his own mysterious patterns. He sometimes uses English, or Kurrent (a relic of medieval cursive script), or even his own invented language to preserve secrecy in shelters and clinics. The paper still smells of tobacco smoke.

Martin is sharp, witty, and very well read; he’s relentlessly honest about himself and his relationships with others, which means many of the movie’s interviewees, and Ivo Zen himself, must confront themselves in a slanted but accurate mirror. Martin’s loved ones read out extracts from the diaries, and discuss their reactions with Zen. Without exception this is very moving, and is perhaps the best testament to the insight and linguistic gifts of the film’s subject. Several interviewees give words to the effect of: “It really was like that – he nailed it.” Zen’s camera captures the blurred realities of his old friend as they arrive via memories on the his interviewees’ faces , prompted by the written word.

“My mother will probably inherit my diaries,” writes the young prophet Martin, “I really hope she enjoys them. Please Mama, don’t miss the ironic undertone. Tragedies should also make you laugh, at least I think so.”

Perhaps Ivo Zen could have let a little more of that laughter burst through his documentary. There’s one great scene in which Martin’s old girlfriend giggles at his complimentary description of her, a time capsule of innocent true love in the midst of life-destroying cocaine addiction.

But I’m not sure Martin was right that tragedies should also make you laugh. Some of them exist simply to help a community process them. In Zaunkönig, as with his follow-up Suot tschêl blau, Ivo Zen does a good job of doing just that, while giving outsiders a glimpse into the brief but life of a one-of-a-kind writer and addict who, were he a teenager today instead of the Platzspitz era, might have survived his fall into addiction.

Swissness Difficulty Level: Säntis (medium).

Language: Swiss German, High German.

Availability: Vimeo VoD, also with English subtitles.

Swissness Lab Report: Heroin 2 (1996-2008) – The Recovery

Zaunkönig and Suot tschêl blau are archives of recent history that also help process it. They face the past more than the present, because things have changed – massively – from the heroin crisis I detailed in a previous review.

An Unholy Alliance

Social workers were going up the wall with “War on Drugs” policing, which led to horrendous stigmatization and not many results. No sooner had the police cracked down on one park scene, it would pop up on the banks of the lake. Finally they reached a stalemate in Platzspitz.

Meanwhile, a Zurich police officer in a recent documentary considers how the new needle exchanges and medical tents at Platzspitz, while saving lives, were also seen as perpetuating conditions of depravity (Addictions, 2023). People at Plaztspitz “didn’t have a reason to leave” while they were getting free clothes, food and drink.

On the other hand you had powerful medical and psychiatric authorities, some of whom favoured a strict abstinence policy or at least had grave doubts about methadone replacement programmes, while others had a much more liberal view.

Finally there were the politicians, whose voter base was influenced by decades of War on Drugs rhetoric as well as media sensationalism from the HIV and AIDS crisis.

Heroin TV and the Out-of-Towners

The visibility of the open drug scene in the media – or anyone passing through train stations or town parks in Switzerland! – disgusted a nation which too pride in orderliness. This was the easiest possible way to make politicians take notice. A decade of scary headlines on HIV and increasing AIDS rates added to the constant background noise.

The TV reports had a negative flipside. They were presumed to have a positive effect on drugs tourism. German celebrity junkie Christiane F has said that Zurich of the 1980s was “like Disney World for junkies”.

You might think this would intensify anti-drug views from the many conservative Swiss voters who lived further from the cities. But those views on drugs had already been the norm for decades, without much success.

And the Stadtpräsident of Zurich at the time said that 80% of people shooting up in Platzspitz were from out of town. They came in from the Kanton, from the rest of Switzerland. In fact, small-town Switzerland had a big problem with its disaffected youth, as we see in Ivo Zen’s movies. Parents were losing their kids; the crisis was destroying conservative families.

1991: Watershed

The crisis wasn’t going away and everyone wanted change. The more liberal social and medical lobby finally made headway with the politicians in 1991 with something called the Four Pillars Approach.

Drug policy in the War on Drugs days revolved around three pillars: Repression, Therapy, and Prevention. In 1991 the government enshrined a fourth, Harm Reduction. They explicitly didn’t propose any courses of action; but they encouraged innovation and round tables. I’ve read this is called “Knowledge Brokering” and “Coalition Building” in the social sciences (Khan et al 2013).

This may not sound like much until you see what it meant in practice. Giving out clean needles as well as methadone maintenance programmes became less up for debate, as harm prevention was normalized.

But most of all, it paved the way for the most controversial change of all.

Swiss Sugar

Methadone, a synthetic version of heroin which had a high which lasted longer and dimmed the effects of heroin, could be useful, but for some addicts it wasn’t enough. They turned back to “sugar”, street heroin mixed with who knows what, shot into their veins, vastly increasing health risks and potential for social damage.

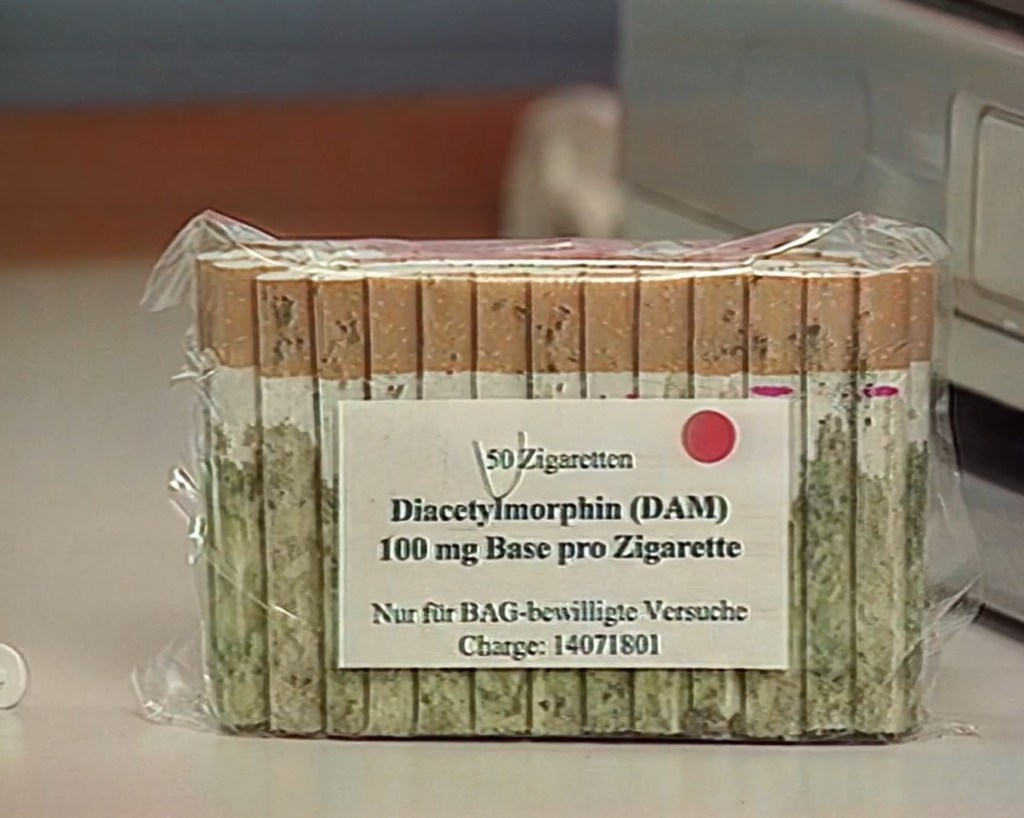

So a pilot study was done with an even more effective drug, called diamorphine.

Diamorphine was very powerful, and had to be taken in supervised injection rooms. It was found to stabilize people’s dosage over two or three months; to reduce people’s consumption of heroin and cocaine (the two drugs complement each other); reduce crime; and increase take-up of other therapies and treatments.

Diamorphine was what these people needed. It helped them, and the state now had proof. The only thing was, diamorphine is heroin. Switzerland had pioneered what is now known as HAT: heroin-assisted treatment.

The illegal drug was produced by the government, in collaboration with poppy farmers from e.g. France or the UK. Nowadays pure heroin, called “diaphin” or shortened to “dia”, is made in a laboratory not far from Zurich, and handed out in supervised sites all over Switzerland.

HAT intermezzo

Before I blather on about direct democracy again, here’s an intermezzo about my other glorious motherland.

Did you know that, in the UK, “diamorphine” is still used in hospitals for things like epidurals? Yes, you can get smack on the NHS as a form of painkiller in certain circumstances. There are opium poppy fields for just that purpose in the Midlands and the South of England (which have also been used to supply the Swiss market!). But the drug remains otherwise illegal to consume in the UK; harm reduction has not extended to HAT; a recent HAT trial in Middlesbrough was successful, but cancelled.

In fact, HAT has only become standard practice in six countries: Canada, Germany, Holland, Denmark, and Luxembourg. As of 2019, Switzerland still consumes 47.2% of the world’s medically prescribed heroin.

After decades of War on Drugs, HAT is a political hot potato too scalding for most countries. How on earth has it stayed the course in good old conservative Switzerland?

Wait, Swiss Democracy Can Also Be Progressive?!

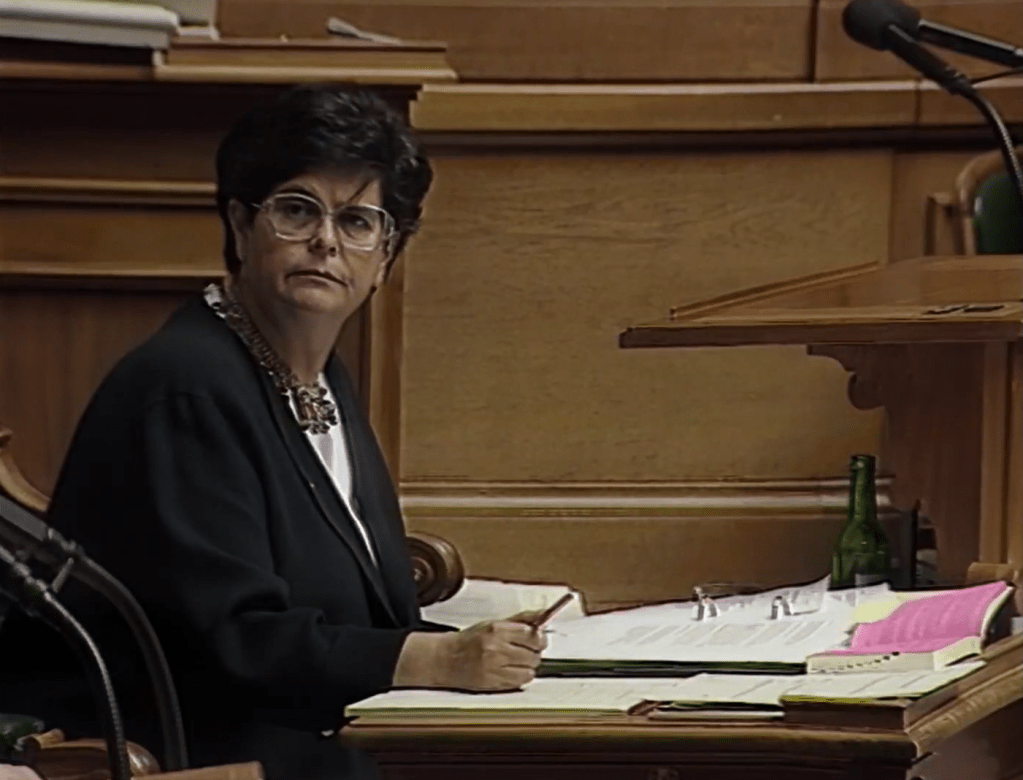

The heroin crisis had got to such a point that cross-party support was mustered for the Four Pillars programme, including HAT, once the evidence came through. Of course, there was a backlash. On the one hand, you had the big Christian, social democrat and neoliberal parties joining up in support of it; on the other, you had the Swiss People’s Party (SVP).

Switzerland being Switzerland, referendums were made. Switzerland being doubly triply Switzerland, they took years to come around.

In 1997 came the “Youth Without Drugs” referendum from the ultra-purist War on Drugs holdovers. The Swiss population roundly rejected this (70.7%).

Then, in 1998, the pendulum swung the other way as pro-drug campaigners tried to build on the momentum. The “In Favour Of A Reasonable Drug Policy” sought to liberalize consuming drugs. Even more of the population rejected that (74%).

Finally the big one came, the referendum on “Heroin Distribution”, i.e. HAT. Most parties were now in favour, apart from the SVP, of course. It got through (54%)!

After three years, the pendulum steadied itself in a centre ground which had been redefined as pro-HAT. By now the fourth pillar of harm reduction was set in stone; everyone agrees in the work the referendums have legitimized HAT, and harm prevention in general.

It’s even been argued (Khan et al, 2014) that the Swiss government’s consensus politics (no opposition party, powerful regions, shared executive power, proportional representation, etc.) was well suited to all the “knowledge brokering” and “coalition building”. It just took a long time to get through, in which time Letten happened and many people died or suffered terrible damage.

Number-Crunching Radical Change

In the mid-Nineties 75% of people considered drugs an important topic. Now it’s at around 10%.

The Four Pillar system, including HAT, achieved huge, demonstrable successes:

– The number of new heroin users declined from 850 in 1990 to 150 in 2002;

Csete 2010: 3

– Between 1991 and 2004, drug-related deaths fell by more than 50 percent;

– The country witnessed a 90 percent reduction in property crime committed by drug users;

– The country that once led Western Europe in HIV prevalence now [in 2010] has among the lowest rates in the region.

The Four Pillars worked, and direct democracy’s systems cooled the scalding spud of controversy. But it took a long time to get there.

Quo Vadis, Swiss Drug Policy?

In the year I came to Switzerland (2008), the first referendum posters I saw were drug-related. The ebullient SVP were trying to crack down on drugs again in one referendum; and the left were pushing for decriminalization of cannabis. As in the late nineties, both referendums were roundly rejected (70%+), confirming the status quo.

The 2023 Swiss documentary Addictions uses the first forty minutes of its 50 minute runtime giving an overview of the Swiss heroin crisis and its recovery. But the last ten minutes it devotes to something else. It states that:

As of today, 900 million Francs have been spent every day on the Four Pillars law.

65% goes to Repression,

26% to Therapy,

5% to Harm Reduction,

4% to Prevention.

The filmmakers clearly promote less money going to Repression, in favour of the Harm Reduction.

Decriminalization would be a logical step. Even in America, where the modern War on Drugs has its roots, cannabis has been legalized for medical use in 38 states; in 24, you can be gettin’ high, just for fun. In this respect, Switzerland is lagging behind. Portugal, not Switzerland, has become the poster child for the liberalization of drug laws in Europe.

One option remains the decriminalization of cannabis. We don’t have it so bad: at the moment you don’t get fined for possession of small amounts, and it’s a straight CHF 100 fine (no criminal charge) for medium amounts. Medical cannabis is permitted, but insurance doesn’t cover it. Trials on recreational cannabis have been going on since 2021; a friend is taking part. So maybe the evidence from that will affect policy soon.

A more urgent need is to focus on regulating newer problem drugs in Switzerland, especially crack cocaine.

But it took a catastrophic, very visible crisis to spur radical change the first time around. Looking back at the Swiss history of change, I can’t see that happening until conservative voices are confronted once again with the need to get with the times.

References:

Addictions (2023 documentary, available on PlaySuisse)

“From the Mountaintops” (2013 social policy report)

“Understanding Swiss Drug Policy Change and the Introduction of Heroin Maintenance Treatment” (Khan et al 2014)

“‘This is hardcore’: a qualitative study exploring service users’ experiences of Heroin-Assisted Treatment (HAT) in Middlesbrough, England” (Riley et al, 2023)

Platzspitzbaby mini-documentaries (2020, from its website)

Articles by André Seidenberg, from his website

Article on 25 years post-Needle Park, from Sozialarchiv.ch

‘I Will Die Soon; I Know That’: Meeting the Real Christiane F (Vice article that mentions Zurich, Max Daly, 2013)

My referencing above is patchy, and bibliography is scruffy because I find this part boring. But if you want more specifics on where to find information, please write to me, I’m doing a lot of research into this topic at the moment (start of 2024) and may be able to help.