Goalie’s middle age arrived with the sound of a judge’s hammer. He’s just spent a year in Witzwil prison, for the only bit of crime he ever did in his life. Not that he’d achieved anything of note before that – bumming from job to job, never too far from his various addictions. But now he’s determined to go clean, stay off the heroin, and get a proper job.

In search of new warmth, it’s only natural Goalie’s thoughts turn to Regi, the kind-hearted waitress in his local dive bar. She gets Goalie a drink on the house and lends him fifty Francs to set him on the right path. And she seems open to a man who seems genuinely a nice guy, with a witty turn of phrase, who makes a change from her usual clientele – and her nasty boyfriend Budi.

Meanwhile, Goalie rekindles friendships with old pals: the junkie Ueli and the esoteric dealer Stofer. But in his new, clear-ish state of mind, he notices odd things about them. Did they have anything to do with his prison spell? Has he been “ä zu liebi Siech” – too much of a nice guy?

In the Swiss canon, Der Goalie bin ig stands apart. It’s a working-class outsider movie, giving a voice to the small-time dealers, the boozers, the working stiffs paid by the hour to drive around packages, because with their reputation, no-one else will have them. But it doesn’t idealize the working classes, à la Bäckerei Zurrer, nor philosophize about them, as in La Salamandre; and it doesn’t play things for sentimentality, like Platzspitzbaby‘s triumph over adversity. It just tells a story.

In the original novel by Pedro Lenz, story-telling is a central theme. Goalie constantly rattles off anecdotes or philosophizes on the curious folks around him. This trim film version concentrates mainly on the two big narrative strands: the romance with Regi, and the mystery of Goalie’s prison sentence.

The choice works less well with the romance. The two actors have lovely chemistry, which makes it all the more disappointing when scenes ends abruptly, or peter off. The conspiracy story, though, is more engaging. It is the real Swiss heart of the story: the reasons for Goalie’s prison time revolves around scapegoating, around fishy bank business, and around the paranoia that comes with tight communities.

Where this film shines brightest is character and setting. Goalie is a really interesting person to follow. He’s a very nice man, agreeable, witty, and with a strong set of morals. He’s also plagued with addiction. He’s never far from booze; in most scenes he’s either smoking or finding ways to eat sweet food (a famous trait of heroin addicts). And he’s naive, sometimes wilfully so. His strengths and flaws are each worn on his sleeve; you can easily understand why a Regula might fall for him, but also why she might have some serious doubts. Marcus Signer, who people will know as the legendary Kägi in Wilder, is pitch-perfect for the role, and won a deserved gong for it at the 2014 Swiss Film Awards.

The setting is small-town, German-speaking Switzerland of the 1980s. Pedro Lenz’s fictional “Schummertal” is based on his home town of Langenthal, which was the main shooting location for the movie. You can really smell the tobacco smoke in Goalie’s apartment, the heroin smoke in the kitchen of his hepatitis-ridden junkie friend, and the stench of bitter rumour and nefarious trade in the local bars.

So all in all, a strong recommend, and a movie that does justice to its source material thanks to attention to detail and powerful performances.

Interestingly, Pedro Lenz’s original novel was written not in German but in Swiss German dialect. In preparation for my rewatching of Goalie, I had a go at reading the novel. If you’d like to know what it’s like to read dialect, read on below!

Swissness Difficulty Level: Chasseral (easy).

Language: Swiss German, of course!

Availability: Not currently on PlaySuisse; I streamed it for a small fee on Vimeo, which has English subtitles but poor quality. It’s easy to find other streams online, though.

Swissness Lab Report: Reading in Swiss German Dialect

I’m a reader, and I’m bilingual. But that doesn’t mean I sit around reading Goethe all day.

I’ve probably read about twenty novels in the language. Some of those were children’s novels, like The Never-Ending Story. Generally, I don’t find reading in German as fun as English. I don’t get as sucked in; it’s harder.

Of those twenty, three or four were by Swiss German authors. They wrote in Standard German, so the experience was almost exactly the same as if I was reading a German or Austrian author. There are only a couple of teeny differences when the Swiss brandish their quill: they don’t like the the Eszett (ß) for some reason, so their “street” is the strasse, not the straße; and they import a couple of their most used words into the standard language, so Fahrrad (“bike”) becomes Velo.

But Der Goalie bin ig by Pedro Lenz is a whole novel in transcribed spoken dialect. This is a really interesting challenge.

The Opening Lines of Der Goalie bin ig

Have a look at these, the first lines of the novel. Read them a couple of times first, to get a feel for it before we get into the nitty gritty.

Aagefange ets eigentlech vüu frücher. Aber I chönnt jetz ou grad so guet beoupte, es heig a däm einten Oben aagefange, es paar Tag nachdäm, dasi vo Witz bi zrügg cho.

Even if you don’t speak “normal” German, these two sentences should seem sort of Germanic, with their consonant clusters ch and tz, vowels with umlauts, and familiar morphemes like be- and -ge-. There are even some recognizable words from school German lessons, like Aber (German for “but”), and paar Tag (“couple of days”).

But then some odd letter combinations complicate things. The aa of aagefange might be Dutch or Flemish, I guess. The vüu is really quite strange. And what is going on with the word zrügg?

Finally, it’s surprisingly hard to identify the subjects (“I”, “he”, “it”, etc.). You might notice the I in the second sentence is the same as in English. Isn’t it funny, though, how the title of the book, Der Goalie bin ig, spells that word differently? And you probably missed that that same subject occurs six words from the end in a different form, as part of dasi.

The es in the es heig could well be the English “it” – in fact it’s the same in Standard German. But did you pick up om the second word, ets, contains the same word, but combined with the verb “have”? Yes, Angefangen hat es (“It started…”) becomes Aagefange hat es which, in the Bernese dialect, sounds more like Aagefange ets.

Let’s compare it to the High German translation of Der Goalie bin ig. I got this from the Amazon.de “Read Sample” function. For ease of reading, I’ll repeat the Swiss German original first, then give the translation.

It actually started much earlier. But I could just as well say that it started on that one evening, a couple of days after I got back from Witzwil prison.

Der Goalie bin ig opening lines, my translation

Aagefange ets eigentlech vüu frücher. Aber I chönnt jetz ou grad so guet beoupte, es heig a däm einten Oben aagefange, es paar Tag nachdäm, dasi vo Witz bi zrügg cho.

Der Goalie bin ig, actual opening lines

Angefangen hat es eigentlich viel früher. Geradeso gut kann ich aber auch behaupten, es hat an diesem einen Abend angefangen, ein paar Tage, nachdem ich aus Witz zurück war.

Der Goalie bin ich, opening lines of the translation by Raphael Urweider

The second one is rather informal German as I learnt in language school, or that you might have learnt in classic school German lessons. The many differences between that and the dialect version include phonology, morphology, vocabulary, and grammar. It’s really its own language.

I’ve learned to understand Swiss German differences, slowly but surely, when listening to people speak. And by osmosis, they crop up when I’m speaking German to Swiss Germans. But I can’t sustain Swiss German speech for long, and when I do it sounds nothing like Lenz’s Bernese dialect – it’s more like Züridüütsch, dialect from Zurich.

Swiss German Text Messages, AKA Dialect Boot Camp

Fortunately, I had some training in understanding Bernese dialect, as I have a good friend who spoke Bärnerdüütsch with me from the moment we met, and who writes her text messages in Swiss German.

Let’s analyse her. 😊

Here’s a recent example. I’ve arranged to meet my friend at the train station. We have arranged a meeting point. Suddenly she writes:

She has to shop to replace her laddered tights (“kaputte strumpf”), so suggests we change our meeting point.

She writes similarly to Pedro Lenz, especially with the vowel sounds and the replacement of “ll” with “u”, so German schnell (“quickly”) becomes Bernese schnäu, whereas in Züridütsch it would, I guess, be schnäll.

But my pal is inconsistent with capitalization. Standard written German would capitalize all the nouns, but she only capitalizes the words she spells in Standard German, i.e. Gleis (platform) and Treffpunkt (meeting point). Why she does this is unclear, for the moment! In the novel, Lenz consistently capitalizes nouns, like in Standard German. In text messages that’s not common. It turns out there’s a good reason for the capitals, which you’ll see shortly!

My pal also wrote this bizarre vowel in the second message: üüs. This is the third person plural reflexive pronoun – it translates literally as “We meet ourselves”. In German, it would be uns. Her version genuinely does resemble the way she says that word. But I checked, and Pedro Lenz normally writes it as üs in the novel.

There are two possible reasons for this. Firstly, the word is not standardized; they just tried to transcribe the sound that they themselves hear, and they found two different ways to do it – üüs and üs.

Secondly, my friend is from the city of Bern, whereas Lenz is from outside it. Small differences between dialects in neighbouring valleys are widespread, because the language has never been standardized. For example, Lenz uses Jo to mean “Yes”, whereas someone from Bern city would write Ja. That kind of nuance is hard for non-native speakers to get.

Not Feeling Like a Farmer

When I contacted my friend to make sure I could show the world her text message, she said yes, but then started looking critically at her own work.

“It’s just sometimes,” she wrote, “I have autocorrect on.”

In fact, she would have written träffpunkt, had her phone not corrected her– that solves the mystery of the High German Treffpunkt, and also explains why Gleis was capitalized.

I was going to leave it there, but then she said something interesting.

She’s lived in the Canton of Zurich for many years now, far from home. “And I have to say that with people round here I don’t write in my real dialect any more.”

You’re saying that wasn’t real “Bärndütsch”, Bernese Swiss Dialext?

Exactly, she says, I would say ä kabuttä Strumpf instead of e kaputte Strumpf.

Excuse me?! Ä kabuttä? That sounds like a Finnish sandwich.

So then she writes the whole message for me again, but this time in what she calls 100% bärn. Here are the two versions next to each other.

I’m nipping into Coop City at the station. I’ve laddered my tights. Shall we just meet on the platform or at the meeting point after all?!”

My English translation

I ga no schnäu is coop city im bhf. I ha e kaputte Strumpf. Träffe mir üüs i dämfau gliich bim Gleis oder Treffpunkt?!

What she actually wrote (how she writes to “all of her Zurich people”)

I ga no schnäu is coop city bim bhf. I ha ä kabuttä Strumpf. Träffä mr üüs i dämfau gliich bim gleis odr träffpunkt?!

Her “100% Bern” version (how she would have written if I was from Bern and she had her autocorrect off

Now, you might not think there’s much difference between the two. It’s mostly a question of accent, or how individual sounds are pronounced – the main things are that the schwa vowel e becomes ä, and that she doesn’t include the vowel sound before the r in mir and oder.

So why would my friend from Bern bother with this kind of “self-censoring” when people from Zürich would understand her perfectly? Well, she can answer that in one sentence:

If she didn’t tone down her dialect, she’d feel like a farmer!

I find this stuff fascinating. This is a woman from the capital city of Switzerland, born and raised in an urban environment, with city-girl street smarts. Her friends in the Zurich area often come from more rural areas than she does. But because her dialect is non-standard here, she actively censors the “strength” of her accent – or rather, she merges it with the dominant Zurich accent – because here, it might sound like she laddered her tights when milking cows. Less 100% Bern, more 100% Barn!

What It Really Feels Like to Read Dialect

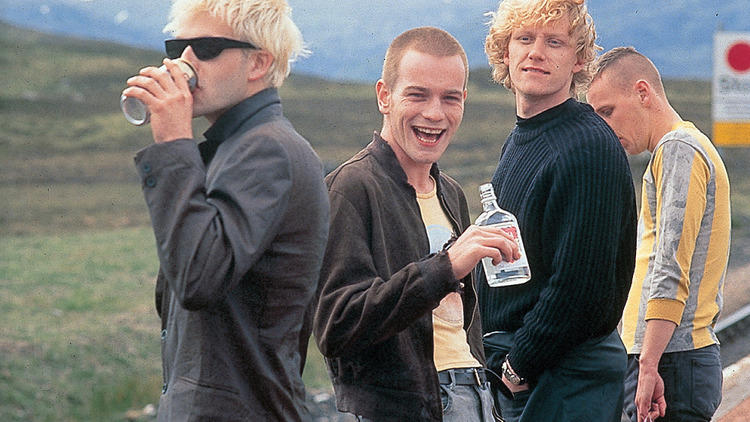

For anyone who speaks English outside of Scotland, have you ever read Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh? You may remember that some of it looks like this:

Ah couldnae mention the Barrowland gig tae Lizzy. No fuckin chance ay that man, ah kin tell ye. Ah had bought ma ticket when ah got ma Giro. That wis me pure skint.

Trainspotting, “Scotland takes drugs in psychic defence” (p71)

As you can see, parts of the book are written in a transcribed variety of Scots accent, with some features. So, take that, crank it up about 75% in terms of difference to English – including more weird vowel combinations, more dialect words you’ve never heard, and consistent effort to “Scotify” any rogue Standard British English. And make that consistent for the course of a whole novel (Trainspotting only uses it sporadically).

When approaching that kind of text, you might find you start by sort of whispering to yourself, imagining the character in your mind’s eye, based on the movie (above) or a Scottish person you know, and how they would say the words. After a few sentences you sink into it.

And that’s how I begin reading Der Goalie bin ig. I start with this inner whispering – reading out the lines in my mind. I can clearly imagine the tone and timbre of the guy’s voice. I’m imagining Marcus Signer, the actor from the movie, because I’ve seen him in quite a few things. Because the novel is told in an anecdotal mode, with many scenes of our man drinking and chatting to people, it becomes very intimate, like you’re sat in the pub and he’s telling you stories. This is absolutely in keeping with the themes of the novel.

It also matches some of the little tricks Lenz has up his sleeve. He’s a gifted technical writer, who grew up bilingual with Spanish and studied language at university.

One of his choices was to avoid using speech marks completely. The whole novel is in first-person point-of-view, floating freely from Goalie’s descriptions of what’s going on in the present, to his reflection on what happened earlier, to actual dialogue between him and other speakers of Bernese dialect. His inner monologue in Swiss German blends into the dialogue, and vice versa. The brew of interactions and contemplations is made all the murkier for the way in which Lenz plays with time, sometimes staying in the present, before catching up with the recent past, plunging us into a flashback, and landing us groggily into the next jaunt to the bar or late-night phone-call.

I should say that none of this is confusing. Goalie’s narration is very clear and simple. He tells things straight, and his pub philosophizing reduces everyday interactions down to pithy conclusions. The vibe is very much: “Now, I’m a simple man, but it seems to me that…”

And this is not an action-packed book. Goalie’s attempts to solve the mystery and win the girl revolve around happenstance, patiently wandering from A to B and seeing what happens.

Wouldn’t This Novel Work in Standard German?

Just to recap, overall, we get a simple, clear prose style, a narrative which wanders off sleepily into the recent and distant past before staggering back into the present, and a fluid transition between speech and thought. This is a really cool and effective combination for two reasons.

Firstly, it is a good approximation of the mind and life of addict. Goalie orders a Kafi Fertig (coffee with schnapps) on page one and spends the rest of the book either tipsy, drunk, or hungover. His thing is downers – booze, sleeping pills, and heroin – and the sleepy, associative style reflects that.

Secondly, it reflects that other crucial part of Goalie’s life – his love of a good story. Here lies one of Goalie’s fundamental weaknesses:

…At some point, she had an overdose of my stories. And when that happened, she accused me of not doing anything but talking, instead of listening, for once. And most of all, she said that I’m not even talking about myself – no, I’m just telling some story.

Der Goalie bin ig p128, my translation

This accusation is made at a key point in the book, towards the end of Act Two. And after that, when Goalie does start listening to people, he must admit the extent of how they’ve been taking advantage of him. And the reader, having been seduced by Goalie’s stories for so long, now realize just how important they are to him, and how they protect him from the abyss.

This moment of revelation can only occur in the reader if the book is written in Swiss German – the language of Goalie’s stories, and the language of his broken heart.

References:

Pedro Lenz, Der Goalie bin ig (2010)

Irvine Welsh, Trainspotting (1993)

Excellent film review! I’ve seen the movie twice, it’s very popular with my sort of demographic. The novel is also very good, but somehow my attention span wasn’t long enough to read that as well.

LikeLike